Concorde’s retirement in 2003 brought the curtain down on an era of supersonic passenger flights. Now, two decades later, Boom Supersonic is trying to revive that era. It’s not just about the speed, the technology, or the glamour, says its CEO—something even more important is at stake.

“Imagine a future in which our children have friends from other continents that they actually spend time with and what that does for the world,” Blake Scholl told Newsweek. “It’s very hard to go to war with somebody you’ve met.”

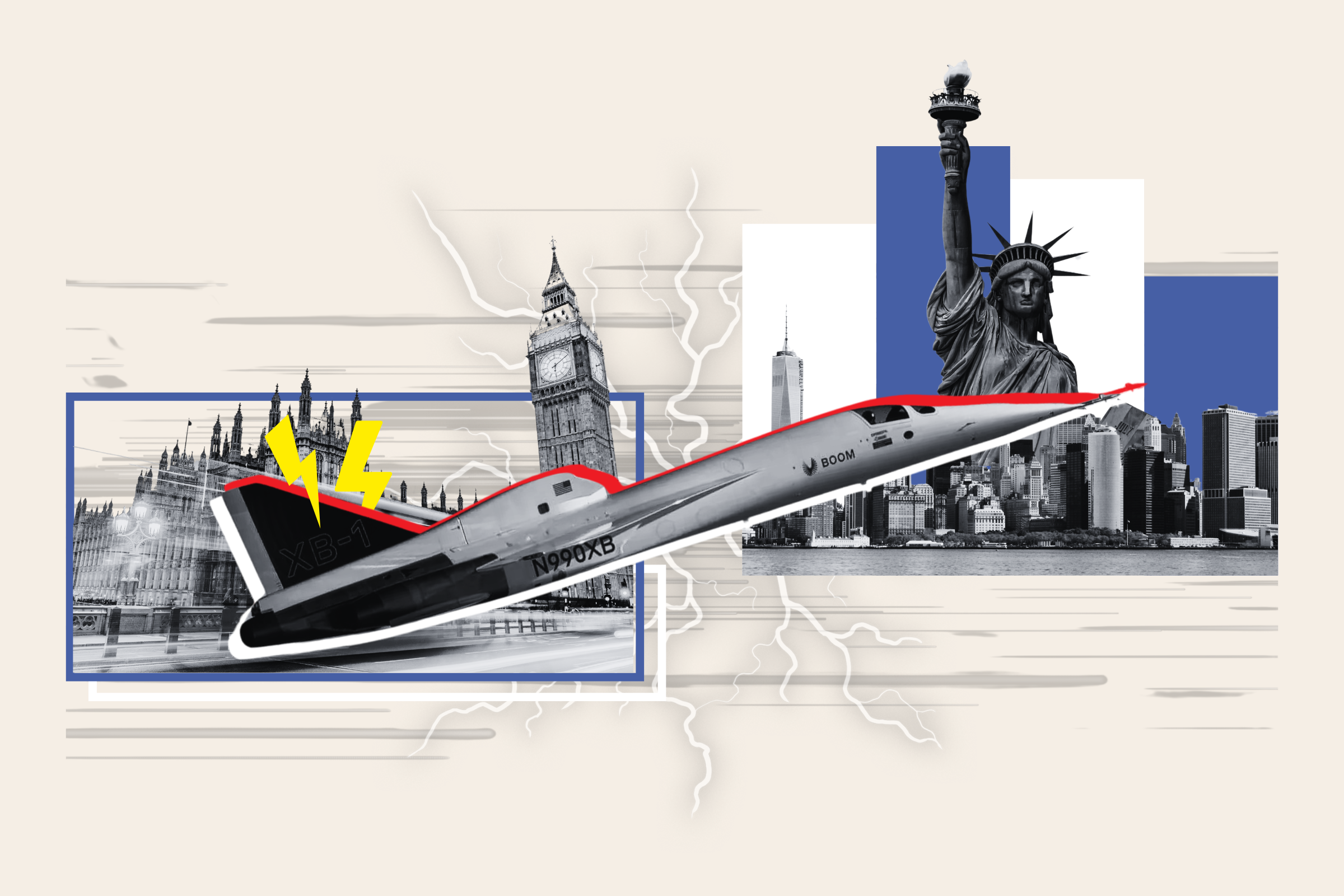

That prospect is edging closer. Tests for the Boom Overture, a spiritual successor to Concorde that could fly between London and New York in just three-and-a-half hours, have taken place throughout January, with plans to revive the original Atlantic journey and open up other supersonic routes across the world.

With those high-profile tests using a dedicated demonstrator jet, Boom’s ambitious project is rekindling excitement about commercial supersonic flight. But beneath the optimism lies a complex web of engineering puzzles, regulatory challenges, and the daunting task of building an entirely new engine.

The Legacy of Supersonic Travel

The first steps toward commercial supersonic travel began in the 1960s, an era defined by bold technological feats and acute international rivalry. The Soviet-built Tupolev Tu-144 debuted just ahead of the Anglo-French Concorde, but it was Concorde that truly captured the public imagination. First flown in 1969, Concorde’s inaugural commercial flight in 1976 transformed aviation by shrinking transatlantic travel to around three hours, giving wealthy passengers a glamorous, if expensive, way to hop between Europe and the United States.

Despite its fame, Concorde was constantly struggling through financial turbulence. The aircraft was limited to flights over water, due to the disruption a sonic boom generates, and after a period of limited profits and a disaster that killed 113 people in 2000, combined with declining public interest, the program was retired in 2003. Supersonic travel had gone out with a whimper.

Photo Illustration by Newsweek/Boom Supersonic

Boom Supersonic’s Vision

Fast forward 22 years, and Boom, the company developing the Overture, is confident that it can navigate those pitfalls to make supersonic flight sustainable and accessible.

“I think the world will be far better off if everybody can fly faster,” Scholl told Newsweek. “This is what makes the world a smaller place. Faster flight determines where we can vacation, it determines where we do business. It even determines who we can fall in love with. I think it is hard to under-appreciate how important that is.”

Scholl founded Boom in 2014, inspired by seeing Concorde in a museum. Before that he worked for technology companies, including Amazon, where he started his career as a software engineer in 2001—the year after Concorde’s infamous crash in Paris.

Development on the Overture began in 2016, with a demonstration model, the XB-1, revealed in 2020. The XB-1, which is roughly a third the size of the final design, has been used for testing, the latest round of which took place in January. The tests made the aircraft the first privately developed jet to break the sound barrier.

Scholl said this testing proved that the technology was capable of breaking the sound barrier without producing an audible shock wave, which was the issue that confined the Concorde to transatlantic flights only.

“The airplane performed beautifully, it actually flew better supersonic than subsonic,” Scholl said. “And we did it with no audible sonic boom, which means you don’t actually have to solve the sonic boom issue by flying over the water.”

This means that Boom’s vision for a far wider range of destinations is a lot more possible; potential routes include San Francisco to Tokyo, which could be made in six hours, and Newark, New Jersey, to Frankfurt, which would be a four-hour flight. For comparison, the same journey by conventional plane takes almost 8 hours.

Boom

For its creators, the technology is a step forward and a revival of aviation history, with many lessons being taken from the Concorde’s successes and failures.

“In the U.K. today and in France, there’s such a deep love of Concorde and what it stood for and this deep sadness that it’s gone,” Scholl said. “We had supersonic flight, and we lost it, and we went backwards. Humanity backslid and that’s not supposed to happen. Concorde showed that supersonic flight was technically possible with 1960s technology. It was 1969 that we landed on the moon, and we flew Concorde for the first time.”

He added: “If you stopped somebody in the street and asked: ‘What do you think space exploration and flight will be like in the future?’ I don’t think anybody would have said that both of those things will be gone.”

As with any commercial project, pricing is one of the most important considerations. In its final days, Concorde was struggling to generate enough money to justify the extremely high development and maintenance costs, despite exorbitant ticket prices.

Boom estimates that starting prices for the Overture would be around $5,000, compared to Concorde’s peak prices of around $12,000, once adjusted for inflation.

Scholl estimated that costs could drop further once the technology was established, saying: “Overture will be very, very profitable for airlines, at more like $5,000. I recognize that’s not yet for every family, but it is tens of millions of people who already pay those prices in business class today, so that’s our starting point.”

He added: “I think a thing that we all have to understand is the way technology works. It needs to start in a relatively higher price point and then as scale happens and innovation happens, the cost comes down.”

Building a Supersonic Engine

Perhaps the most significant technical hurdle for Boom is developing its own power plant, known as the Symphony engine. Boom previously explored partnerships with established engine manufacturers but eventually went in-house, believing a custom solution would more precisely meet the Overture’s thrust, efficiency and noise requirements.

The Symphony engine is designed for supercruise—meaning it can fly faster than the speed of sound without afterburners. Concorde’s engines needed afterburners for takeoff and acceleration, making them far noisier and less efficient. Yet even without afterburners, supercruise comes with its own challenges. It burns far more fuel than standard subsonic engines, especially during the longer climb to higher altitudes and at speeds that generate greater air resistance. Such thirsty performance multiplies greenhouse gas emissions unless powered by sustainable fuels.

To overcome these hurdles, Boom says it has proprietary technology for a specialized engine that can achieve clean, quiet flight at supersonic speeds. Nonetheless, designing, testing, and certifying an entirely new engine poses enormous risk for a relatively young company.

Boom

What Happens Next?

After the successful tests in January, Boom plans to have Overture models rolling out in two years. The aim is for the planes to be passenger-ready in four years, meaning flights could take place by the end of the decade.

It has commitments from multiple carriers to purchase the jet, including United Airlines, American Airlines and Japan Airlines. Boom says it has 130 orders and preorders for the Overture and there is demand for 1,000, compared to 20 examples of Concorde.

However, the global push for supersonic passenger travel has seen its share of high-profile casualties, including Aerion Supersonic, which folded in 2021 despite significant backing, and Exosonic in 2024.

Exosonic CEO Norris Tie told Business Insider after his company collapsed: “Boom has said it would cost up to $8 billion to build its supersonic plane, and that’s a low number. The company has only publicly funded less than $1 billion. It’s a long road, and I don’t know how it’s going to get done.”

There may be many more twists and turns in the supersonic race to become Concorde’s spiritual successor.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)