NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

The State Department informed U.S.-based employees on Thursday that it would soon begin laying off nearly 2,000 workers after the recent Supreme Court decision allowing the Trump administration to move forward with mass job cuts as part of its efforts to downsize the federal workforce.

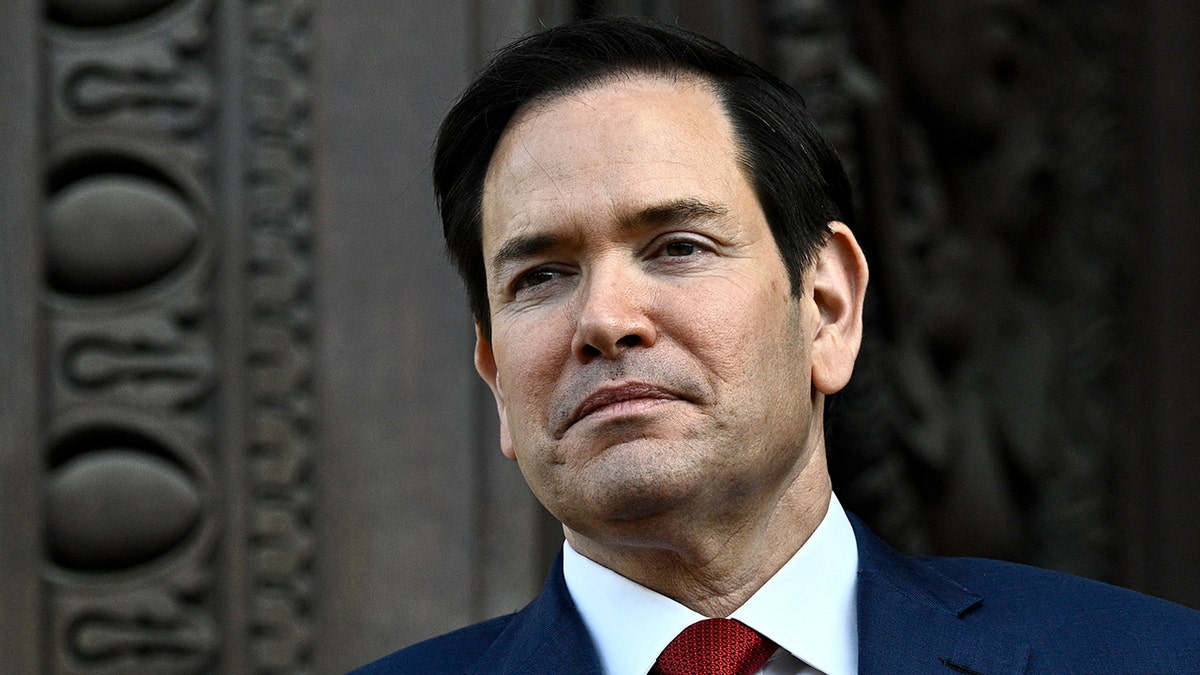

The agency’s reorganization plan was first unveiled in April by Secretary of State Marco Rubio to eliminate functions and offices the department considered to be redundant. In February, President Donald Trump issued an executive order directing Rubio to revamp the foreign service to ensure that the president’s foreign policy is “faithfully” implemented.

Employees affected by the agency’s “reduction in force” would be notified soon, Deputy Secretary for Management and Resources Michael Rigas told employees in an email on Thursday.

‘IT WILL HAPPEN QUICKLY’: STATE DEPT POISED TO ACT AFTER SUPREME COURT GREEN-LIGHTS AGENCY LAYOFFS

The State Department informed U.S.-based employees that it would soon be laying off nearly 2,000 workers. (Nathan Posner/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

“First and foremost, we want to thank them for their dedication and service to the United States,” Rigas said in the email.

“Every effort has been made to support our colleagues who are departing, including those who opted into the Deferred Resignation Programs … On behalf of Department leadership, we extend our gratitude for your hard work and commitment to executing this reorganization and for your ongoing dedication to advancing U.S. national interests across the world,” he added.

The department did not specify on Thursday how many people would be fired, but in its plans to Congress sent in May, it had proposed laying off about 1,800 employees of the 18,000 estimated domestic workforce. Another 1,575 were estimated to have taken deferred resignations.

SOTOMAYOR BREAKS WITH JACKSON IN SUPREME COURT DECISION OVER TRUMP CUTS TO FEDERAL WORKFORCE

The reorganization plan was first unveiled in April by Secretary of State Marco Rubio. (JULIEN DE ROSA/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

The plans to Congress did not state how many of these workers would be from the civil service and how many from the foreign service, but it did say that more than 300 of the department’s 734 bureaus and offices would be streamlined, merged or eliminated.

Once affected staff have been notified, the department “will enter the final stage of its reorganization and focus its attention on delivering results-driven diplomacy,” Rigas said in the email to colleagues.

The expectation is for the terminations to start as soon as Friday.

State Department spokesperson Tammy Bruce told reporters earlier on Thursday that the only reason there had been a delay in implementing force reductions is because the courts have stepped in, as she said the mass layoffs would be happening quickly.

The expectation is for the terminations to start as soon as Friday. (Yuri Gripas/Abaca/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“There has been a delay – not to our interests, but because of the courts,” Bruce noted. “It’s been difficult when you know you need to get something done for the benefit of everyone.”

“When something is too large to operate, too bureaucratic, to actually function, and to deliver projects, or action, it has to change,” she said.

Reuters contributed to this report.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)