From his home in the coastal Israeli city of Bat Yam, Pedatzur Ben-Attiya recalled a time when he used to recruit “spies” to send into Libya.

“It was in the 2000s and early 2010s, when Colonel Gaddafi was still in power,” said Ben Attiya, 62, head of the city’s Libyan Jewish congregation, called Or Shalom. “I would seek foreigners on online forums — it was before social media — who were about to travel to Libya for work, and ask them to travel to specific Jewish sites — without raising suspicions — to take pictures for me and for our community.”

While the task may have seemed largely benign, the mission of checking up on cemeteries, synagogues and other sites came with real dangers.

“Some of our ‘spies’ made it out of Libya easily, some got caught and questioned by Gaddafi’s security services, some were arrested and disappeared, like Rafram Haddad, who got caught and spent five months undergoing torture in Gaddafi’s prisons,” recalled Ben-Attiya, who himself has never set foot in the country his parents left decades earlier.

On Sunday, the fraught nature of Libya’s ties with both its Jewish community and Israel came crashing back when Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen announced he had held a meeting with his Libyan counterpart Najla Mangoush in Rome, sparking outrage in Libya over the unprecedented contact, and a storm of criticism at home over his revelation.

News of the meeting, which Israel said included talks on “the importance of preserving the heritage of Libyan Jews, which includes renovating synagogues and Jewish cemeteries in the country,” aroused contrasting feelings among the Jewish-Libyan diaspora.

For some, the meeting is a prelude to warmer relations between the two countries, giving rise to hope that one day they will finally be able to visit their ancestral homeland, but others rejected any suggestion of reliving past family traumas, their ties with Libya severed for good.

“I do not hate Libyans. They have hurt us greatly, but we Libyan Jews have become a success story in Israel,” said Netanya’s Daniel Mimun, 77, who fled Libya for Italy in 1967 with his family before later moving to Israel. “To me, Libya is just a bad memory that I cannot extricate out of myself.”

An abrupt end to a 2,000-year-long history

The history of Jews in Libya stretches back thousands of years. The first Jewish settlements go back about 2,200 years, predating by centuries the arrival of Arab Muslim conquerors. At the eve of World War II, there were around 40,000 community members in the country, and 25% of the population of Tripoli was Jewish.

While Jews were persecuted and subjected to antisemitic laws under dictator Benito Mussolini — Libya was an Italian colony — and around 700 died in labor camps during World War II, the real decline of the community started after the war. In 1945, following the liberation of North Africa, Jews were subject to pogroms perpetrated by the local population, with 140 killed and most synagogues looted and destroyed in Tripoli. Anti-Jewish violence broke out again in 1948 when the State of Israel was established.

The violence prompted a large wave of immigration, with thousands leaving for Italy or Israel by the early 1950s. The around 2,500 Jews who remained behind were forced to flee in 1967 during the riots that broke out in response to the Six Day War.

In interviews, many Libyan Jews recalled the trauma of the persecutions they suffered at the hands of the local population, and how they “ran for their lives and never looked back,” as one woman put it.

“We were treated like pariahs. Our Jewish religion was marked in our passports. My father owned a business, but our family properties were confiscated by the Libyan authorities. My brothers barely survived lynches by workers in my father’s factory, and we had to flee,” recalled Mimun.

Libya was plunged into chaos after a NATO-backed uprising toppled longtime dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. The oil-rich country has been split between the Western-backed government in Tripoli and a rival administration in the country’s east. Each side has been backed by armed groups and foreign governments. Gaddafi was hostile to Israel and a staunch supporter of the Palestinians, including terror groups.

Despite the bad memories, some Libyan Jews are interested in ties with Tripoli, especially as it may allow the community to preserve its heritage sites.

“I am glad today that I sent those people to take pictures inside Libya, because some of those Jewish religious sites are gone,” said Ben-Attiya. “The Libyan authorities have done nothing to preserve them, and I know of at least one synagogue that we received pictures of and which has collapsed in the meantime.”

Commenting on the possibility of a normalization of ties between Israel and Libya, Ben-Attiya said that he would love to go to visit one day and see with his own eyes the places his family came from, but would never dream of living there. He expressed the wish for the only standing synagogue in Tripoli to be converted into a museum of Jewish heritage.

In Israel, Libyan Jewish identity is mostly expressed through community ties, special foods and religious traditions — such as the Bsisa, a ritual performed by women on Rosh Hodesh Nissan, the first day of the Jewish month of Nissan. There is also a Jewish-Arabic dialect spoken by Libyan Jews, which is used in a magazine put out by the Or Shalom community.

Ben-Attiya described the members of his community as traditional, the kind of Jews that would never miss a synagogue service on Shabbat, but may drive to the beach afterwards.

David Gerbi, a Rome-based psychologist who made an short-lived attempt to restore the Tripoli synagogue a decade ago, envisioned a “Tunisian Jewish diaspora model,” referencing Tunisian Jews, particularly from the island of Djerba, who moved to France but still keep a house on the island, and return for family and religious celebrations such as Lag B’Omer.

“Nobody in their sane mind would think of living in Libya today, but for sure it would be nice to visit more often,” he said.

The abandoned synagogue, known as Dar Bishi, in the Old City of Tripoli, Libya’s capital, April 12, 2015 (Photo by MAHMUD TURKIA / AFP)

‘We cannot forget their cruelty’

Other Libyan Jews reacted with less enthusiasm to the news, or with outright rejection.

Ever Cohen fled Libya in 1967 at age 27, leaving behind a successful auto sales business. He claimed that Jews and Muslims in Libya were incompatible due to “religious and cultural differences.

While he has fond memories of the archaeological and natural wonders of Libya, the Herzliya Pituah-resident did not see the point in pursuing a normalization agreement with the current Libyan government, nor in demanding reparations for lost properties.

Felice Guetta, 62, who also fled Libya for Italy in 1967, said he cannot understand those who feel nostalgia for Libya, adding that the locals’ “cruelty and ferociousness cannot be forgotten.”

Others maintained that Israel has nothing to gain from relations with the North African country, and that its warring rulers are not to be trusted.

“The pillars of Libya’s economic development were Italian settlers and Jews. When Colonel Gaddafi rose to power, he kept the local population unproductive, indolent and ignorant by handing out petrodollars, instead of developing the economy,” said Mimun.

A prominent community member living between Italy and Israel who asked not to be named criticized Cohen’s revelation as a shortsighted move with no purpose other than to shore up his own credentials and possibly to gain votes of the Libyan community in Israel.

The backlash from the announcement may be greater than the benefit, he said, with radical Muslim Libyans possibly attacking Jewish sites in Europe or in Libya itself.

He added that if there were ever a chance for a peace deal with Libya, Eli Cohen’s announcement “set us back by 30 years.”

Libyans hold signs during a demonstration against the presence of Jews in Libya and the reopening of the Dar Bishi Synagogue in Tripoli on October 7, 2011 (Photo by Marco LONGARI / AFP)

Preserving the material heritage

But Gerbi argued that Cohen’s announcement of the meeting with his Libyan counterpart on Sunday was not a diplomatic faux pas but rather a deliberated move coordinated between Israel and Libya. He claimed that the international community, in particular the US, has put pressure on premier Abdul Hamid al-Dbeibeh to hold elections in the next few months, and Dbeibeh intends to ensure US support for his candidacy by making a gesture to America’s greatest ally in the region, Israel.

“That explains the timing of the announcement by Eli Cohen,” he said. “Libya probably wanted to test the water, and see what the popular reaction would be. A few extremists have taken to the streets and have burned Israeli flags. It clearly did not go as planned.”

Gerbi’s history with Libya goes back to 2002, when he entered the country to rescue his aunt, who he thought was dead.

“She was the last Jew left in the country. Our whole family had fled in 1967, but she remained behind with her siblings, as they felt deeply Libyan. Eventually, all her siblings died, she remained alone and she ended up in an institution,” he recalled.

“I discovered she was still alive, and got in touch with her. She begged me to take her out of Libya after she saw what had happened to our Jewish cemetery. It had been completely destroyed, the tombstones stolen and used for construction. Bones of the dead were sticking out of the ground,” Gerbi added.

The psychologist claimed that he wound up facilitating contacts between Gaddafi and the US government, through the mediation of the chief rabbi of Italy at the time, Elio Toaff. In exchange for his aunt’s release, he claimed, he managed to convince officials in the US State Department to soften US policy toward Gadddafi, who at that stage was abandoning his hardcore anti-Western rhetoric.

Gerbi was invited to visit Libya again in 2007, and met with Gaddafi in Rome in 2009. Gerbi used his influence on the regime to seek to preserve the vast Jewish heritage throughout Libya, starting from the last remaining synagogue in his native Tripoli.

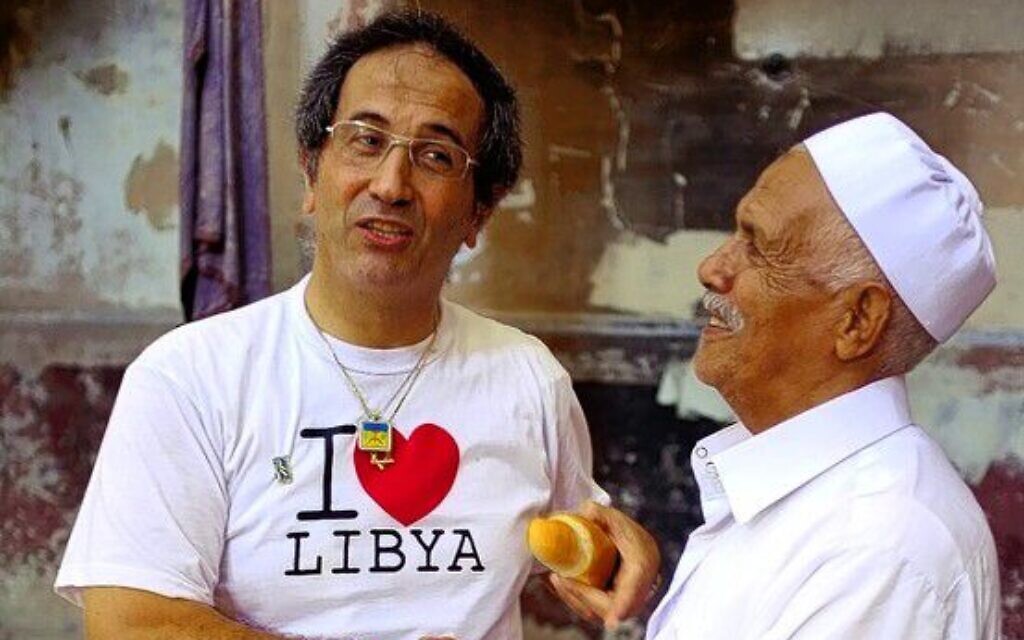

A meeting between Libya’s ruler Colonel Gaddafi (right) and Jewish Italian psychologist David Gerbi, of Libyan descent (on the left), during Gerbi’s visit to Italy in June 2009 (courtesy)

In 2011, during the Arab Spring, in the last months of Gaddafi’s regime, he was invited to work as a community therapist in the town of Jadu, in the northwest of the country, an area inhabited mostly by the Amazigh, or Berbers, ancient Jewish tribes that were converted to Islam but still preserve certain Jewish rituals. Jadu was also the site of a concentration camp run by Italian Fascists where Jews were confined in 1941-42 and over 560 died.

After Gaddafi’s fall later that year, Gerbi delivered a letter to the new government on behalf of the Israel-based World Organization of Libyan Jewish communities, expressing the exiles’ support for freedom and democracy.

Eventually, through diplomatic pressure, Gerbi managed to enter the country more frequently, and achieved his dream of starting restoration work on the main synagogue in Tripoli, an event covered by the international press at the time.

“The outside wall of the temple bore signs of bullets,” Gerbi recalled. “They had been shot by Gaddafi himself against the building. He claimed that Jews had placed demons inside it, and shuttered it.”

The excitement over the restoration project was brief. Local extremists, exposed to Gaddafi’s propaganda machine against Israel for decades, started spreading rumors that Gerbi was an undercover Israeli agent and “the Israeli army was about to invade Tripoli.” Soon after, a mob came to his hotel to lynch him, and he was forced to flee.

Nearly a decade later, in April 2021, Gerbi claimed he was contacted by an assistant to Hussein al-Qatrani, deputy of Dbeibeh, the internationally recognized prime minister of Libya who rules over the west of the country. The prime minister had apparently heard of Gerbi’s intercession between Gaddafi and the US in 2002, and wanted to seek his mediation with US Ambassador to Libya Richard Norland, to obtain US support for Dbeibeh against his rival in the east of the country, General Khalifa Haftar.

A preliminary meeting between Gerbi, the Libyan deputy prime minister and the US ambassador took place in Tunis in early November 2022, and was supposed to be followed up a few weeks later by an official event in Rome, with the attendance of the Israeli ambassador Alon Bar. The Libyan deputy prime minister confirmed his participation, but backed out shortly before the event.

A composite image of Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen (left), and Libyan Foreign Minister Najla Mangoush (right), (Iakovos Hatzistavrou / AFP, Adem ALTAN / AFP)

An orchestrated move between Israel and Libya

“Dbeibeh is a businessman and a pragmatist,” said Gerbi, who also met with Cohen in Jerusalem in March to discuss diplomatic efforts for the preservation of Jewish heritage in Libya.

“He is aware that relations with Israel would bring great benefits to his country, in terms of access to Israeli technology, scientific and agricultural innovations. He wants to join the club of Arab countries who are aligned with Israel and benefit from enhanced relations with the US. I have no doubts that relations with Israel will continue behind closed doors.”

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)