As a boy, Paul Caponigro was obsessed with the little Brownie camera his grandmother used to take photographs of the family. He once said in an interview that he was just 12 years old when he used pocket money to buy his own.

But the camera wasn’t enough.

“He got very disappointed by the little prints that came back from the corner drugstore,” said his son, John Paul Caponigro. “Then he saw some other photographs that were really lively, luminous, and he needed to figure out how to make his own prints. He saw very early that, while you could frame something, making a beautiful print of it was its own art and craft.”

His first darkroom was in the basement of his family home in Boston when he was still just a kid. His last was in his home in the woods in Cushing.

Paul Caponigro died Nov. 10 of congestive heart failure at 91. He became known as one of America’s foremost landscape photographers and an expert in the traditional silver gelatin process he used to create his black-and-white images.

“He is still known today really as one of the masters of analog photography, and he stayed true to it over the years,” said Kari Wehrs, photography program chair at Maine Media Workshops + College in Rockport, where Caponigro taught one of the first classes 50 years ago.

“Running White Deer” by Paul Caponigro, County Wicklow Ireland, 1967. Courtesy of John Paul Caponigro

THE PIANO AND THE CAMERA

Paul Caponigro and Ansel Adams used to sit at the dinner table and argue about classical music composers. (Paul Caponigro would usually make the case that Chopin was the best, while Adams defended Mozart.)

His first love, even before photography, was music. Caponigro was born in 1932 and grew up in Boston. His uncle played piano professionally, and Caponigro told his son about how he would beeline for the bench when the family visited the man at home.

“He wouldn’t even say hello,” John Paul Caponigro, 59, said. “He would just sit down and wait until Jimmy started playing.”

Caponigro’s father decided that his children would all play a different instrument, and he at first dictated that Caponigro would play the accordion, while his sister would play the piano. He brought his young son to pick out her instrument, not knowing that she would quickly give it up while her brother waited patiently to take her place at the keys. He later studied at the Boston University College of Music before he made his career in photography.

The piano and the camera were dual passions throughout his life.

“Both of them said, ‘You have to play with us, think about us, work with us,’” Caponigro said in an interview he and his son did as part of a video series for the printing company for Epson America in 2019. “And I did both. While the prints are washing in the darkroom, I’m upstairs practicing the piano.”

Caponigro became known for the spiritual quality of his work. His subjects include the megalithic monuments of the British Isles, Scotland and Ireland, the temples and sacred gardens of Japan and the woodlands of New England.

His first solo exhibition was at the George Eastman Museum in 1958 and went on to be exhibited internationally. Today, his work is in the collections of such institutions as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Smithsonian America Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

He received two Guggenheim Fellowships and three National Endowment for the Arts grants. He consulted with the Polaroid Corporation. He was awarded numerous honors during his career and was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame this year.

His son said Paul Caponigro lived “by lifting his finger and feeling the wind.” He did not plan his work and preferred to be spontaneous. He didn’t keep a particularly regular schedule. He was rigorous about his process in the darkroom. He did not make a print once and then pack it away. He tried new variations and stayed open to new ideas. He fostered a deep interest in spirituality and endeavored to live simply.

“Like a musician might have practiced so that he knows all his scales, he knows the progressions, he got all that,” John Paul Caponigro said. “But today’s another day. What’s going to happen today? And I think that kept him alive to the process and creating a lively object.”

‘A BIT OF MAGIC’

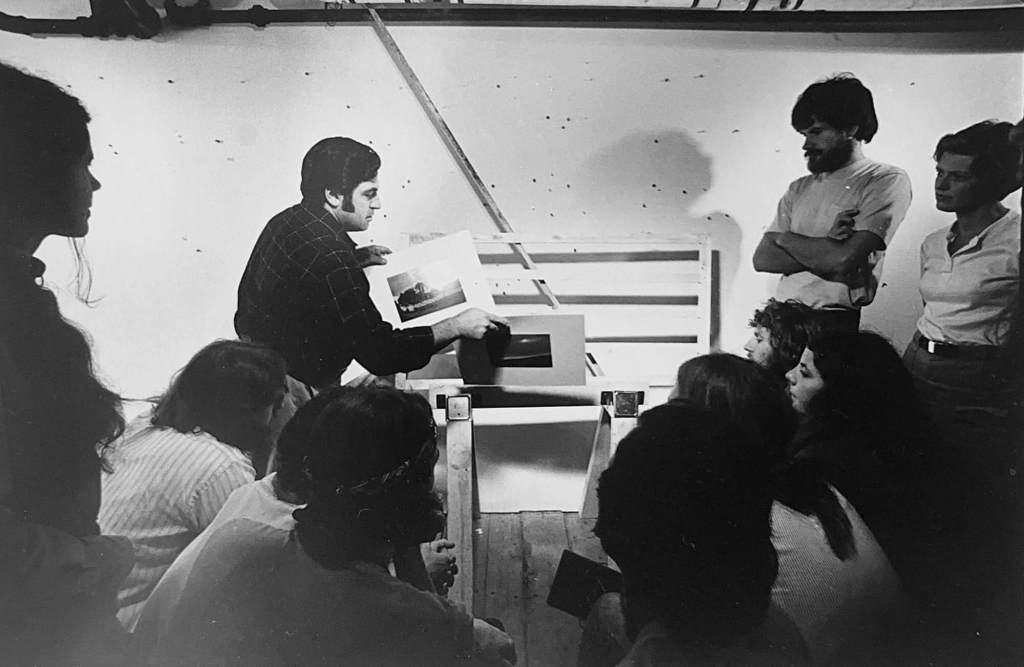

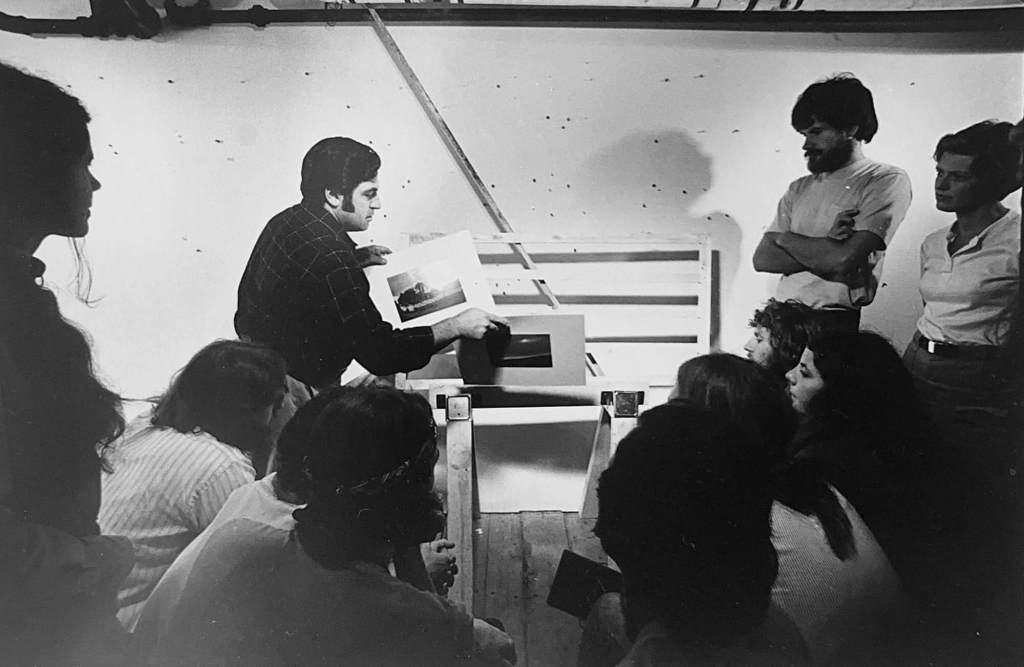

In 1974, Caponigro came to Rockport for the summer to teach at what was then called the Maine Photographic Workshops, now known as Maine Media. Wehrs, who first met Caponigro through Maine Media more than 10 years ago, said she admired his ability to make a photograph “feel like a transformation.”

“I really feel that Paul was able to embody a bit of magic,” she said.

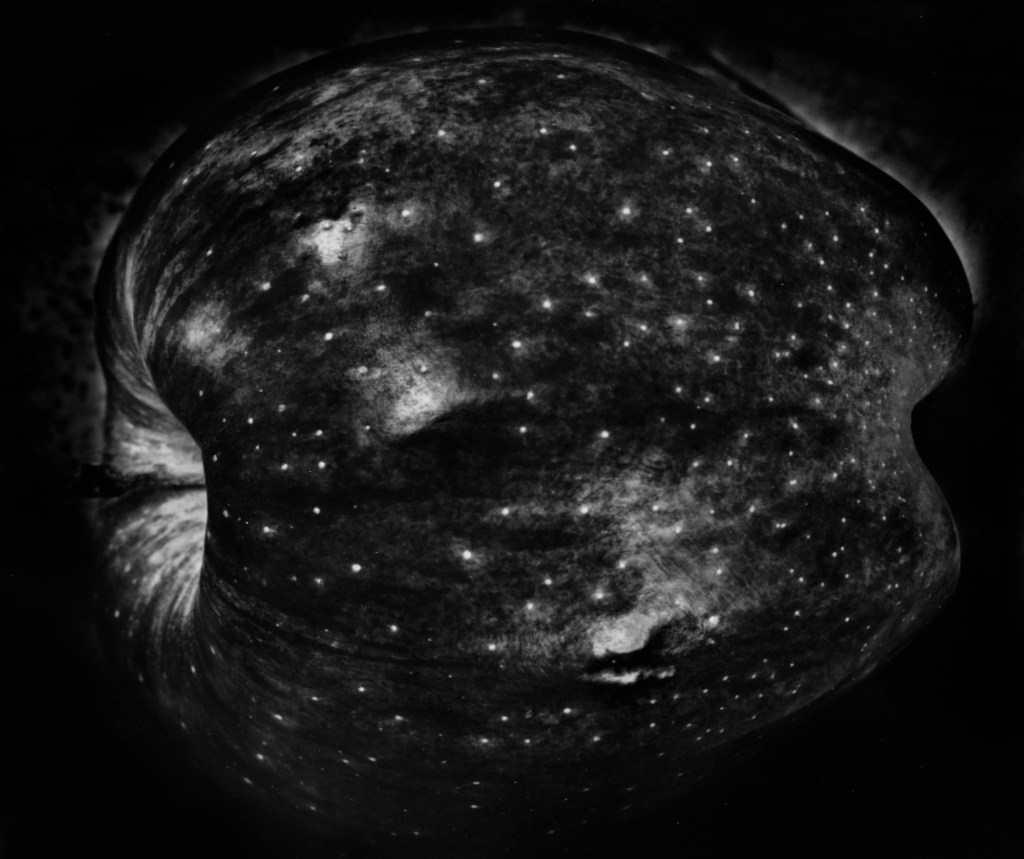

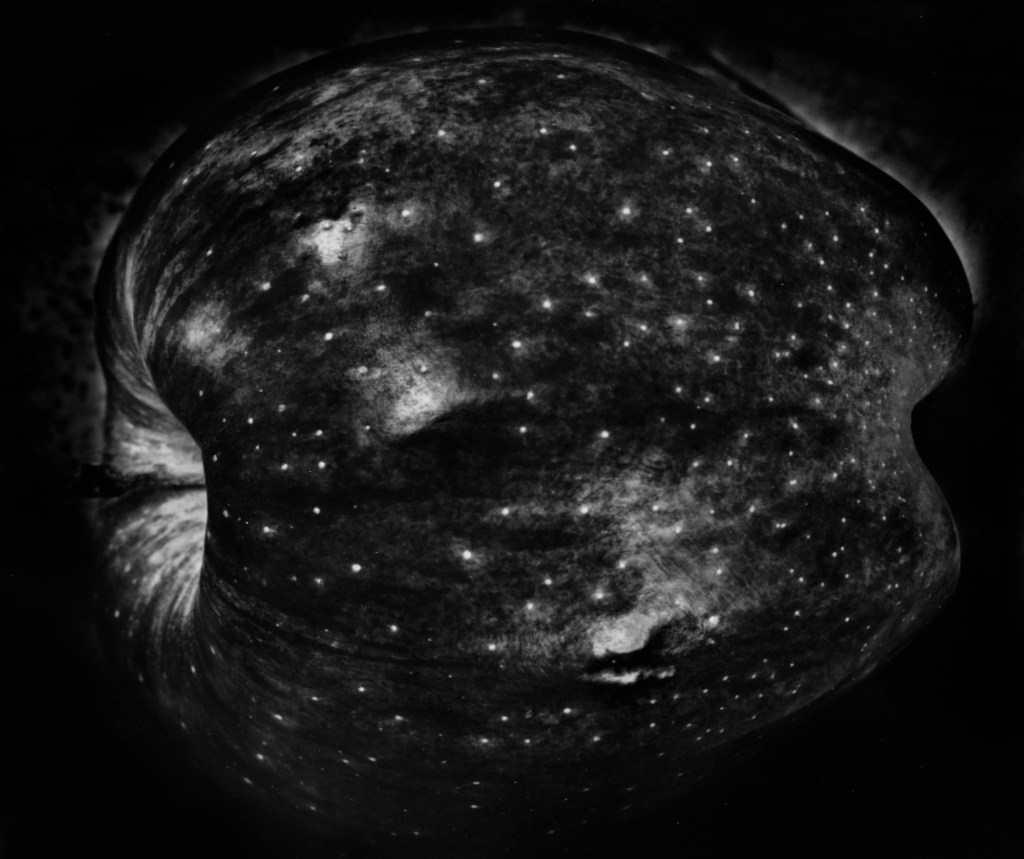

“Galaxy Apple” by Paul Caponigro. Courtesy of John Paul Caponigro

Take the apple. Caponigro made a still life of a solitary apple one day and then made a print that seemed to have a night sky inside the subject. (“This starry sky emerged” in the darkroom, he said in the video interview. “I was only there to recognize it.”)

“He transformed the picture to feel like a galaxy,” Wehrs said. “You feel, in many of his pictures as you’re looking at them, that you understand what the thing is, but if you’re listening, the picture is going to tell you, ‘I’m also something else.’ ”

Over the years, Wehrs brought students to visit Caponigro in his home in Cushing. Once, he taught a full-day workshop in his darkroom for her class. The conversation would be about photography, sure, but also about life itself. Caponigro would ask existential questions. He would answer every question posed to him. Students would often ask him about how to find their own path in photography.

He would answer: “Somebody has to be you, and you’re the closest person to it.”

Paul Caponigro teaches a workshop at Maine Media in 1974 when it was known as the Maine Photographic Workshops. Photo courtesy of Maine Media Archive

‘ALIVE TO THE PROCESS’

As a boy, John Paul Caponigro would listen as his father would jokingly accuse his friend Adams of having a secret “cloud stick” to command the skies for his iconic photographs. The child, maybe 6 years old, once excused himself in order to snoop in Adams’ camera bag for this magic treasure.

His family was one of art and music. From a young age, he was always drawing, informed also by his mother’s work in painting and graphic design. Once, when his dad got a Guggenheim Fellowship to support a project in Ireland, they moved into a Dublin apartment.

“I took up mural making and almost got us kicked out of the apartment,” John Paul Caponigro said. “I tease my parents that they paper-trained me. They put blocks of paper in every room and said, ‘Hey kid, on the paper, not on the wall.’ ”

The family lived in Connecticut and New Mexico as he was growing up. His parents divorced in 1976 when John Paul Caponigro was 12 years old but remained “fast friends,” he said.

John Paul Caponigro said his father never pushed him toward photography, and he didn’t seriously explore it until college. Digital tools captured him in the way the analog ones had his father; he joked that he finally got his “cloud stick” when he discovered Photoshop. John Paul Caponigro moved to Maine in 1989, and his father moved into a neighboring house in Cushing a few years later.

They showed their photography together over the years and often talked over breakfast about music and art. John Paul Caponigro is working on a collaborative book with essays and photos by both of them, which he hopes will publish next year. Their techniques and styles were vastly different, but they could still speak the same language.

“It was never about technique,” he said. “It was more about the internal experience of the art, where it took us emotionally, the poetry of the thing.”

“Alignment II” by John Paul Caponigro. Photo courtesy of John Paul Caponigro.

HERE AND NOT

When John Paul Caponigro entered his father’s home for the first time since his death, he sat down at the piano and played a while. He didn’t plan a specific tune, just kept things simple as his father would have.

“There were very few times in our lives where we didn’t live close to each other, in the same area,” his son said. “The body’s not there, but the house, the piano is. The spirit is. To some degree, he’s in me. The prints on the wall, they’re there. He’s not here, and he is.”

Father and son talked in their interview with Epson America about their different processes – one analog, one digital.

“I’m so glad you have a lot of years left, and you’re going to do all that stuff,” Paul Caponigro said. “I’m going to slowly melt away with silver.”

“Thank god he’s that way,” his son said with a smile. “Can you imagine how much tech support I’d have to do if he went digital?”

They laughed together.

“You’re a good kid,” Paul Caponigro said and wrapped his arm around his son. “Fine boy. Fabulous artist.”

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)