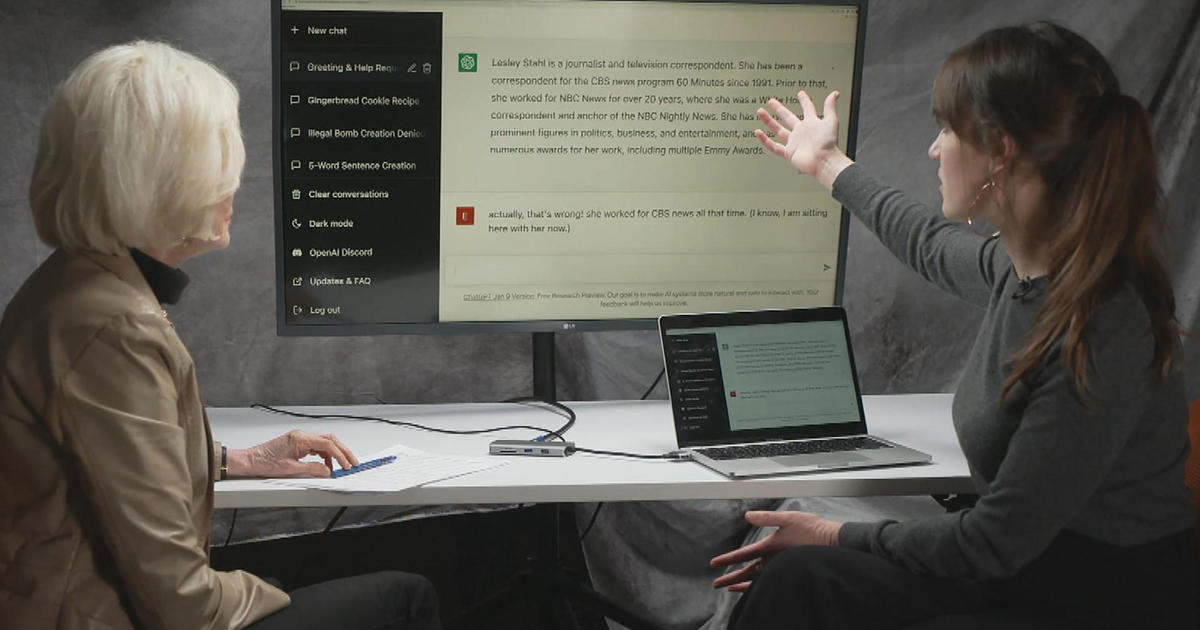

ChatGPT, the artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot that can make users think they are talking to a human, is the newest technology taking the internet by storm. It is also the latest example of the potential for bias inherent in some AI.

Developed by the company OpenAI, ChatGPT—a generative pre-trained transformer (GPT)—is one application of a large language model. These models are fed massive amounts of text and data on the internet, which they use to predict the most likely sequence of words in response to a prompt. ChatGPT can answer questions, explain complex topics, and even help write code, emails, and essays.

However, the answers given by tools like ChatGPT may not be as neutral as many users might expect. OpenAI’s CEO, Sam Altman, admitted last month that ChatGPT has “shortcomings around bias.”

Systems like ChatGPT have produced outputs that are nonsensical, factually incorrect—even sexist, racist, or otherwise offensive. These negative outputs have not shocked Timnit Gebru, the founder and executive director of the Distributed Artificial Intelligence Research Institute.

Gebru’s research has pointed to the pitfalls of training artificial intelligence applications with mountains of indiscriminate data from the internet. In 2020, she co-authored a paper highlighting the risks of certain AI systems. This publication, she said, led her to being forced out as the co-head of Google’s AI ethics team.

As Gebru explained, people can assume that, because the internet is replete with text and data, systems trained on this data must therefore be encoding various viewpoints.

“And what we argue is that size doesn’t guarantee diversity,” Gebru said.

Instead, she contends, there are many ways data on the internet can enforce bias—beginning with who has access to the internet and who does not. Furthermore, women and people in underrepresented groups are more likely to be harassed and bullied online, leading them to spend less time on the internet, Gebru said. In turn, these perspectives are less represented in the data that large language models encode.

“The text that you’re using from the internet to train these models is going to be encoding the people who remain online, who are not bullied off—all of the sexist and racist things that are on the internet, all of the hegemonic views that are on the internet,” Gebru said. “So, we were not surprised to see racist, and sexist, and homophobic, and ableist, et cetera, outputs.”

To combat this, Gebru said companies and research groups are building toxicity detectors that are similar to social media platforms that do content moderation. That task ultimately falls to humans who train the system on which content is harmful.

To Gebru, this piecemeal approach—removing harmful content as it happens—is like playing whack-a-mole. She thinks the way to handle artificial intelligence systems like these going forward is to build in oversight and regulation.

“I do think that there should be an agency that is helping us make sure that some of these systems are safe, that they’re not harming us, that it is actually beneficial, you know?” Gebru said. “There should be some sort of oversight. I don’t see any reason why this one industry is being treated so differently from everything else.”

In the months since ChatGPT’s debut last November, conservatives have also accused the chatbot of being biased—against conservatives. In January, a National Review article said the chatbot had gone “woke.” It pointed to examples, including a user asking the bot to generate a story in which former President Donald Trump beat President Joe Biden in a presidential debate, and the bot’s refusal to write a story about why drag queen story hour is bad for children.

ChatGPT’s maker, OpenAI, has said they are working to reduce the chatbot’s biases and will allow users to customize its behavior.

“We’re always working to improve the clarity of these guidelines [about political and controversial topics],” the company wrote in a blog post last month, “and based on what we’ve learned from the ChatGPT launch so far, we’re going to provide clearer instructions to reviewers about potential pitfalls and challenges tied to bias, as well as controversial figures and themes.”

The video above was produced by Brit McCandless Farmer and Will Croxton. It was edited by Will Croxton.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)