The last time anyone saw Marine Corps Sgt. James Edmund Johnson, he was fighting with all his might in frozen North Korea to make sure his fellow Marines could get away from an enemy that would have ravaged them. Johnson never made it home from that battle, but his fighting spirit and unwavering devotion led him to receive a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Johnson was born on Jan. 1, 1926, in Pocatello, Idaho, to John Johnson and Juanita Hart. He had an older sister named Cleo.

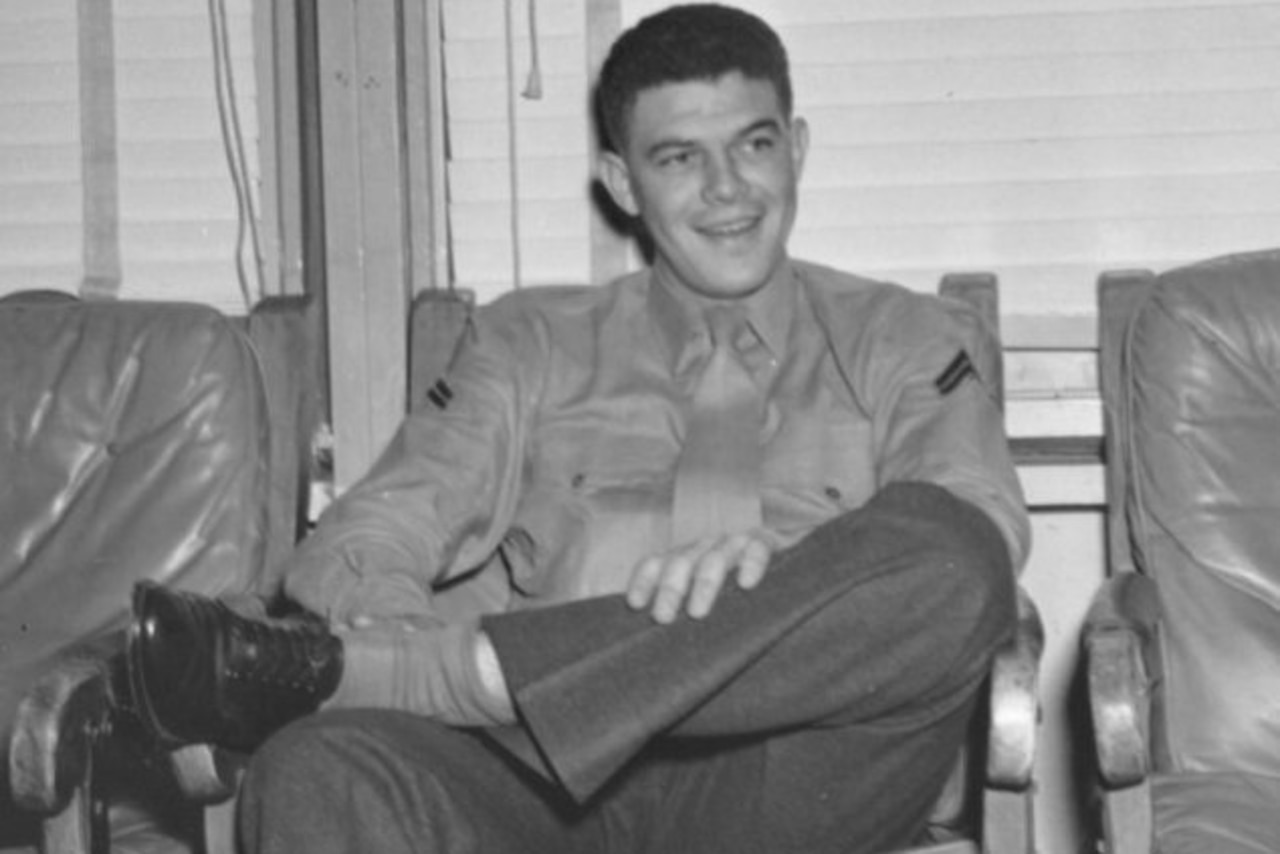

Johnson grew up attending public schools. He played junior varsity basketball in high school for two years before dropping out to enlist in the Marine Corps on Nov. 10, 1943.

World War II was in full swing at the time, so Johnson was sent to the Pacific theater, where he participated in the Peleliu and Okinawa campaigns. After the war ended, he was discharged and returned home to Pocatello, where he went to work as a machinist at a naval ordnance plant.

According to a 1951 Salt Lake Tribune article, Johnson then attended Western Washington College in Bellingham, Washington, so he could study business administration. His studies didn’t last, however, as he reenlisted in the Marines in January 1948.

After reintegration, Johnson took an assignment at Quantico, Virginia, where he met a woman named Mary Jeanne. They married on Oct. 15, 1949, before Johnson moved to Washington, D.C., to serve as an instructor in post exchange accounting at the Marine Corps Institute.

Shortly after the Korean War broke out, Johnson was called up to the front. He left for the peninsula in August 1950, five days after the birth of his daughter, Stephanie.

As an artilleryman, Johnson was normally assigned to the 1st Marine Division’s 11th Marines, the same regiment his father served in during World War I. However, during the United Nations push to the Chosin Reservoir in the fall of 1950, Johnson was provisionally placed with the infantry of the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines.

During the bitter Chosin Reservoir campaign, the 7th was in Yudam-ni in northeast North Korea on the western side of the reservoir. Johnson was serving as the squad leader of a provisional rifle platoon made up of artillerymen who were attached to Company J.

On Dec. 2, 1950, the platoon was ordered to attack Chinese forces on Hill 1542, but they were vastly outnumbered by a well-entrenched enemy, which had managed to conceal themselves in the uniforms of friendly troops. Johnson’s platoon was in open, unconcealed positions, and they were vulnerable to the attack.

Left without a leader, Johnson didn’t hesitate to step up and take charge of the platoon. In his Medal of Honor citation, he reportedly “exhibiting great personal valor in the face of a heavy barrage of hostile fire, coolly proceeded to move about among his men, shouting words of encouragement and inspiration and skillfully directing their fire.”

When the platoon was ordered to withdraw, Johnson was told to cover his fleeing men while the firefight continued. He quickly moved into a position to do so, even though he was fully aware that the precarious location meant he would die or be captured.

Johnson courageously provided effective cover fire so his entire platoon could retreat safely. He was last seen suffering from wounds but continuing to engage the enemy in hand-to-hand fighting. Johnson never got to rejoin his platoon, but his valiant and inspiring leadership was directly responsible for saving many lives during the withdrawal.

Johnson was listed as missing in action afterward. When it was announced in December 1951 that he would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions, leaders said the award was being made “in absentia” in the hopes that he would one day be able to come home and receive it in person.

Unfortunately, that homecoming never happened. Nearly two years later, on Nov. 2, 1953, Johnson was listed as presumed dead. So far, his remains have not been recovered.

Johnson’s Medal of Honor was finally presented to his widow during a Pentagon ceremony on March 29, 1954. Two other Marines also received the high honor that day: Sgt. Daniel P. Matthews and Cpl. Lee H. Phillips.

Johnson’s name is listed on the Wall of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii. There is also a memorial marker in his honor at Arlington National Cemetery.

A replica of the sergeant’s Medal of Honor is on display at the Bannock County Veterans Memorial Building Museum in his hometown, where Johnson has not been forgotten. In 1963, the naval ordnance plant where he once worked was reconstructed and named the Johnson Armed Forces Reserve Center. In 1984, the Marine Corps named a street on Camp Pendleton, California, after him.

This article is part of a weekly series called “Medal of Honor Monday,” in which we highlight one of the more than 3,500 Medal of Honor recipients who have received the U.S. military’s highest medal for valor.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)