November is Native American Heritage Month, providing Defense Department leaders with an opportunity to recognize the remarkable achievements of Indigenous peoples throughout our nation’s history.

Last week, Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks delivered a short address to champion Native contributions to national security, highlighting Medal of Honor recipients of Indigenous descent — including Jack Montgomery, Ernest Childers, Pappy Boyington and Woodrow Keeble — who each served valiantly in conflicts spanning decades of American military service.

Since our country’s inception, Native Americans have demonstrated a unique commitment to this nation. Among their contributions stands the legacy of the Oneida Nation, whose support for American independence saw the Continental Army through its lowest point in the Revolutionary War. As patriots struggled to shed the tyranny of monarchial rule, the Oneida set a precedent for honor, loyalty and selflessness that Indigenous peoples have carried forward for centuries.

The Oneida Nation’s Indomitable Legacy

Amid the chaos of the American Revolution, the Oneida, one of the Iroquois Confederacy’s six tribes, formed an alliance with Gen. George Washington and his embattled Continental Army. With the war’s outcome far from decided, the Oneida risked their own independence and survival by committing to the American cause. The tribe’s decision ultimately saw Washington through the darkest hours of his command — and rescued an army on the brink of collapse.

While the Oneida Nation maintained friendly relations with the colonists throughout the Revolution, British aggression inspired the tribe to take up arms on behalf of their American neighbors.

In the summer of 1777, a coalition of British regulars, Loyalists and Mohawk warriors threatened to march through Oneida territory to attack American forces at Fort Schuyler, New York. After years spent defending themselves from indigenous rivals and European influence, the Oneida considered the incursion an affront to their sovereignty. Recognizing that their fate was intertwined with that of the patriots, the Oneida pledged their loyalty to the Continental Army on the eve of the British attack.

Oneida fighters’ support was both timely and tangible. On Aug. 2, 1777, they raced to Fort Schuyler to warn the soldiers of the impending siege. Four days later, they fought alongside the New York militia at Oriskany — one of the bloodiest battles of the Revolution. Despite sustaining heavy losses, the Oneida and their allies turned back the British coalition, preventing them from building the combat power necessary to thwart the Continental Army’s decisive victory at Saratoga.

While the Oneida’s performance at Oriskany earned the tribe its rightful place in American history, their contributions to the Continental Army extended well beyond the battlefield.

In December 1777, Washington marched his army to their winter quarters at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. His men arrived at the makeshift encampment exhausted, hungry and sick. The garrison’s poor conditions exacerbated their problems. Washington’s men quickly exhausted their remaining supplies battling the bitter winter — a threat as formidable as their British enemy. Morale, and trust in Washington’s resolve, faded. Faced with mounting desertion, the embattled general turned to the Oneida, nearby farmers and his friends in the Colonial Army for support.

Washington revealed his desperate situation in a letter to Brig. Gen. George Clinton. “[Though] you may not be able to contribute materially to our relief, you can perhaps do something towards it,” he pleaded. “[Any] assistance, however trifling in itself, will be of great moment, at so critical a juncture, and will conduce to keeping the army together.”

Clinton offered no reprieve — his soldiers were no better off than Washington’s. And the farmers outside Philadelphia offered little help — their faith in independence waned once rumors of desertion escaped Valley Forge. Only Washington’s indigenous allies answered his call.

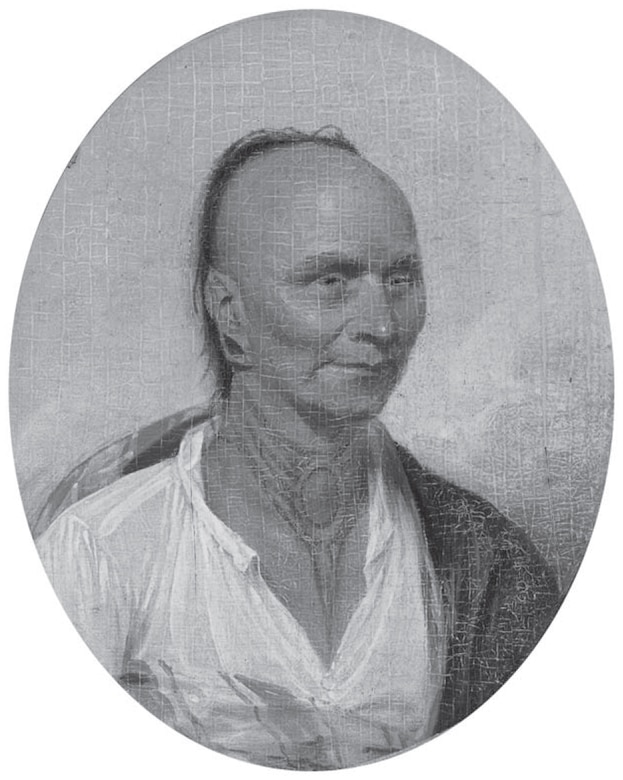

In January 1778, Oneida warriors descended on the encampment laden with food and supplies. Polly Cooper, an Oneida woman skilled in cooking and medicine who accompanied the party, taught the soldiers how to properly prepare hundreds of baskets of white corn, saving many from starvation.

Cooper remained at Valley Forge throughout the winter without promise of payment or reparation, providing care to Continental troops, including their commander. Months later, Martha Washington expressed her gratitude by presenting Cooper with a shawl and bonnet — a gesture which underscored her husband’s reverence for the Oneida people and their outsized contribution to the Continental Army’s survival.

Washington’s relationship with the Oneida was built on mutual respect and shared ideals. As his army recovered, he dined with Oneida leaders and presented each with a wampum belt as a symbol of indelible friendship.

The Oneida’s alliance with the Continental Army was born from their own commitment to liberty. Several years after the war, Oneida Chief Good Peter spoke of the ethos that inspired his peoples’ support for the American cause. “The love of peace — and the love of our land which gave us birth — supported our resolution [to fight alongside the patriots],” he said.

For the rest of the war, the Oneida served as scouts, soldiers and spies. They patrolled the perilous forests surrounding Valley Forge, gathered intelligence on British movements and intercepted enemy communications. Ten Oneida soldiers received officers’ commissions in the Continental Army — a testament to their valor, leadership and competence.

However, the tribe’s allegiance came at a great cost. Oneida villages were pillaged by Mohawk war parties, whose alliance with the British caused internal strife within the Iroquois Confederacy.

In the wake of the revolution, Congress expressed gratitude to the Oneida for their assistance, granting them reparations and relative peace. And while that gratitude did not always translate into equitable treatment, the Oneida’s legacy persisted.

During Native American Heritage Month, the Defense Department celebrates the Oneida by commemorating their loyalty during a critical point in our nation’s history. The Oneida’s role in the Revolution is in line with countless other Indigenous contributions to America’s defense — the whole of which embodies the transcendent spirit upon which our nation is founded.

In her address, Hicks noted that today, Native Americans remain instrumental to “maintaining the finest fighting force in the world,” and their legacy of service punctuates our shared American experience.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)