On the morning of Memorial Day in 1969, two young women disappeared after spending their holiday weekend together in Ocean City.

Susan Davis and Elizabeth Perry, both 19, had been staying at a boarding house and stopped at the Somers Point Diner on their way out of town, around 5:45 a.m. The two college friends were expected to travel together to Pennsylvania and then North Carolina to visit their families, but they never showed up to their first stop at Davis’ parents’ home near Harrisburg.

Three days after the girls went missing, their bodies were discovered in a wooded area about 200 feet from the northbound lanes of the Garden State Parkway, not far from the diner, near mile marker 31.9.

Both women had been stabbed multiple times and showed signs of being severely beaten. Davis was found undressed with her clothes in a pile beside her. The crime scene was about 150 yards from where police had earlier found Davis’ abandoned Chevy convertible, which had been towed before it was known Davis and Perry were missing.

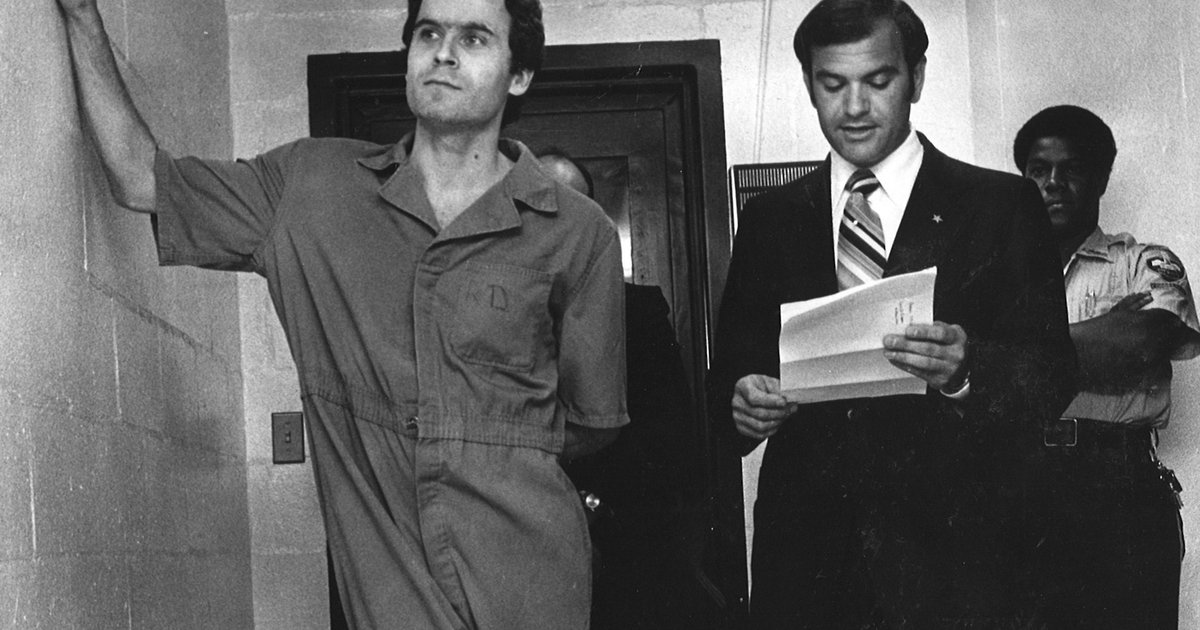

More than 50 years later, their killer has never been found, but a prevailing theory is that the 19-year-olds were the first victims of serial killer Ted Bundy.

The murders were the subject of an episode of Oxygen True Crime’s new series “Violent Minds: Killers on Tape,” which premiered Sunday night. The show delves into the recordings of interviews conducted with serial killers, including Bundy, Arthur Gary Bishop and the men behind the Hi-Fi murders in Utah in 1974, among others.

To this day, the case of the Garden State Parkway murders consumes the minds of true crime sleuths for one glaring reason: Bundy, the notorious serial killer who has ties to Philadelphia and the Jersey Shore.

Bundy was born in Vermont and is often remembered for his formative years in the Pacific Northwest, but part of his childhood was spent in Philly with his mother and his grandparents, who had a home on Ridge Avenue in Roxborough. Bundy also attended Temple University for a semester at the beginning of 1969, a few months before the Garden State Parkway murders. At the time, he was living with his aunt at a home in Lafayette Hill, Montgomery County. His maternal grandparents owned a home in Ocean City, where he would often visit as a boy.

Bundy’s main connection to the these killings is a recorded interview in which Bundy said he was at the Jersey Shore during the “early summer” of 1969. He stated he had “picked up a couple of young girls” for what “ended up being the first time.” Those remarks have inextricably tied Bundy to a case that has haunted the investigators and the families of the two victims for the last five decades.

A treasure trove of Bundy recordings

Ted Bundy was on death row in Florida in 1986 when, during a tape-recorded conversation with forensic psychologist Al Norman, he suggested that he killed Susan Davis and Elizabeth Perry. At the time, Norman had been working on an appeal for Bundy and had earned his trust. Bundy confided in him about his trip to the Jersey Shore in 1969.

During his interviews with forensic psychologists, Bundy was known to alternately speak about the events in his life in the first-person and the third-person. He would spill cryptic details about his past and his violent motivations, leaving researchers with a complex picture of Bundy’s reality and his delusions of grandeur.

“Violent Minds: Killers On Tape” is based on a treasure trove of recordings left behind by the late, pioneering forensic psychologist Dr. Al Carlisle, who traded archives with Norman as they each examined the psychology of serial killers. This was around the time when the FBI was just beginning to develop its Behavioral Analysis Unit dedicated to understanding these crimes, which had entered a so-called Golden Age.

The Norman tape that includes Bundy’s allusion to the Garden State Parkway murders was among the recordings that Carlisle’s family found after the psychologist died in 2018.

“The family wants this to be a living library, and it’s been distributed to law enforcement and forensic psychologists,” Kathryn Vaughan, the showrunner for Oxygen True Crime series, said in a recent interview.

Many of the tapes in Carlisle’s collection were previously unheard, although some, including Bundy’s, had been transcribed in years past.

When he first met Ted Bundy in 1976, he was still in the early stages of his career. Carlisle was given the job of assessing Bundy’s mental makeup after Bundy was arrested for the botched abduction of a woman in Salt Lake City in 1974. Bundy had been convicted and was assigned to a state program to undergo a 90-day psychological evaluation that would help determine his prison sentence.

At the time, Bundy was a handsome and charming student in law school at the University of Utah, and his crime appeared to be out of character.

“It was a standard assignment to evaluate a really run-of-the-mill convicted criminal — a guy who, at that point, had been convicted of one kidnapping,” Vaughan said. “Everybody was writing the judge saying, ‘(Bundy) is a great guy. This must have been a mistake. This guy’s a law student.'”

But Carlisle, who was developing his theory on the rise of serial killers, became convinced Bundy was a serious threat to the public.

“Carlisle didn’t get fooled by Bundy. He saw through Bundy even though he really was suspected to be not that big of a criminal,” Vaughan said. “He went in to the judge and said Bundy was an incredibly dangerous person.”

The principles of Carlisle’s theory were rooted in his Mormon faith, and his pool of research subjects came from the Utah State Prison system.

“In his religion, he was taught to believe everyone is good — full stop,” Vaughan said. “It’s nurture, not nature. You are not born evil, you are born good. His true mission, and his work to uncover the development of the violent mind, was about what turns that. If he could determine and pinpoint the moment when someone turned, could that help in the future with a person who was maybe was heading down that path?”

Based on Carlisle’s recommendation to the judge, Bundy was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Within months, Bundy displayed his uncanny ability to evade justice. He briefly escaped the prison and was then placed in solitary confinement.

Carlisle, who had not recorded his meetings with Bundy, never again made the mistake of not taping his interviews with violent criminals.

“He was really doing this on his own, without a manual or sort of instruction how-to list,” Vaughan said of Carlisle’s work.

By the time of his imprisonment, Bundy had become a suspect in several unsolved murders elsewhere in the country. In 1976, he was transferred from Utah to Colorado on charges connected to the killing of a young nurse. There, Bundy made his most daring escape in 1977, climbing through the ceiling of his cell at the Garfield County Jail. He was able to eventually make his way to Florida, where he murdered two women at a Florida State University sorority house and then abducted and killed a 12-year-old girl a few weeks later.

“But for the fact that Bundy was an incredible escape artist, Carlisle’s evaluation would have saved those women in the Chi Omega house,” Vaughan said.

‘A different insight’ into a serial killer’s mind

The episode of the new TV series that examines the Bundy tapes includes interviews with Christian Barth, an author and attorney considered an expert on the Garden State Parkway murders.

In 2020, Barth published “The Garden State Parkway Murders: A Cold Case Mystery,” in which he examines the many angles and intricacies of the investigation. His years of research includes interviews with police, prosecutors, the families of the Davis and Perry, and even Bundy’s aunt from Lafayette Hill, among many others.

Barth provides an exhaustive account of the various suspects who have been connected to the Jersey Shore slayings, evaluating the plausibility of the connection each had to the crime.

Although there’s strong evidence that points to a different killer, Barth said he still cannot rule Bundy out — and neither can investigators in New Jersey.

“My line has always been that no evidence has been presented to me, nor have I found anything in the course of my decades-long research, to exclude Bundy,” Barth said.

Barth, who was 3 years old in 1969, recalls the first time he learned of the murders was when he overheard his parents talking about them during a drive the shore back to their home in Cherry Hill.

“It’s one of those buried childhood memories. We were driving home, and I remember my mother leaning over to my father and saying, ‘They never found out who killed those girls, did they?'” Barth said.

Before the filming of “Violent Minds: Killers On Tape,” Barth only had read transcripts of the killer’s interview with Norman in 1986.

“This is the first time I got to hear the tapes. You’re able to gather a different insight and give it some context and some shape based on intonation, spaces in speaking, things along those lines,” Barth said. “Bundy was very clear. He just came out of nowhere and made these remarks.”

Officially, Bundy confessed to killing, kidnapping and raping more than 30 women in seven states between 1974 and 1978 — mostly in the western part of the country and in Florida. His gruesome crimes in the Panhandle region, in and around Tallahassee, were ultimately what led to Bundy being sentenced to death.

Still, many Bundy researchers believe his true number of victims is significantly higher than what he admitted to, and that his violent tendencies may have begun years before his first known murders.

This suspicion was only amplified by Bundy’s time on death row, when he seemed to take glee in divulging much of his personal history to his psychologists and attorneys.

For researchers like Barth, who have tried to develop profiles of Bundy’s life and crimes, the recurring references to incidents at the Jersey Shore in 1969 have become a focal point. No matter how vague Bundy was, his remarks offer a compelling lead for those hoping to uncover more about his story — and possibly aid in seeking justice for the women who died.

The investigators of the Garden State Parkway murders lost years of precious time, in part, because Al Norman was unable to speak openly about his conversations with Bundy until after the serial killer was executed in 1989. The hint of Bundy’s possible involvement wasn’t on the radar of Atlantic County prosecutors until 20 years after Davis and Perry were killed. Disturbed by the way Bundy’s remarks lined up with their deaths, Norman disclosed what he knew to authorities about the chance of Bundy’s connection.

Norman wasn’t the only researcher who knew of this grave possibility.

The day before Bundy was executed, during an interview with criminologist Dorothy Lewis, he again alluded to a crime at the Jersey Shore. Barth said he has seen the transcript of this interview, but he has never heard a recording.

“For whatever reason, Bundy clarified his (prior) remarks to Norman in that interview,” Barth said. “Bundy said it was 1969 and he was in Ocean City. He really, specifically said Ocean City this time. He said to Lewis that he tried to abduct a woman on the beach, but she got away from him.”

In the hours before he was killed, Bundy recanted what he had told Lewis. Police were never able to corroborate an attempted abduction. Barth still finds this strange. Presumably, a victim would have notified police that a man had tried to kidnap her.

“That person has never been heard from,” Barth said.

Although Bundy’s credibility was questionable, Barth said Norman firmly believed Bundy was truthful with him, in general. Otherwise, Norman would not have felt compelled to go the police.

But there are some reasons to be skeptical of Bundy’s imprecise language. The fact the he referenced the “early summer” of 1969, instead of the spring, is at least a little bit confounding. Memorial Day marks the start of the annual shore season, which is associated with the unofficial start of summer, and years had passed by before Bundy ever brought it up to Norman. It’s possible his memory was misplaced.

What stands out most to Barth about the interviews with Norman and Lewis is that Bundy mentioned the Jersey Shore, both times, without either of the interviewers asking him anything about about it or leading him to that discussion.

“It was completely extemporaneous,” Barth said.

‘Closure and Justice’

In many of his interviews, Ted Bundy famously referred to his impulse to kill as “The Entity,” a dark part of his mind that repeatedly drove him to violence.

“That’s how he would characterize this almost palpable force developing in his head that he was unable to control,” Barth said. “He said it was fueled and facilitated by the exposure to pornography combined with violence.”

During interviews with Bundy’s aunt, Barth learned that Bundy frequently traveled from Lafayette Hill to New York City on weekends to immerse himself in Times Square’s bustling Mecca of pornography in the late 1960s and 1970s. Bundy was particularly drawn to grinder films that depicted sex and violence together.

Furthermore, Bundy’s aunt told Barth that when Ted was a young boy, he often went to his grandparents’ home in Ocean City, which was in the area of 26th Street. Barth was able to verify a photo of Bundy at a fishing pier in Ocean City when he was a kid.

“According to his aunt, Ted had been down there many, many times over the years,” Barth said. “To the extent that serial killers tend to hunt in an area with which they’re familiar and comfortable, that would certainly lend itself to the conclusion that Ted had scouted this area long before the murders.”

Barth acknowledges that Bundy does not explicitly admit to killing Perry or Davis in the tapes. And from his own research, Barth knows there are details about other suspects in the case.

By sheer coincidence, for example, one suspect named George Stano was on death row in Florida with Bundy. Stano had been convicted of killing at least 22 women in New Jersey, Florida and Pennsylvania. He confessed to killing Davis and Perry outside Somers Point, but Stano had a reputation as a “serial confessor” and police didn’t fully believe him, Barth said.

Over the years, Barth has gotten numerous tips from people who claim they saw Bundy in Ocean City over the weekend of the murders. One man swore he saw him enter a hospital on the morning Davis and Perry were killed. Barth said the man’s account was convincing, although the lack of photographic evidence has always stymied advancement of that theory.

“Trust me, I get a few kooks who call me with Bundy sightings,” Barth said. “He wasn’t one of them.”

As the years pass by without an answer, Barth is aware that the window to solve the case is slipping away. Many of the retired detectives he interviewed have since died, and police are hampered in sharing hard evidence due to state disclosure laws.

“I think when a case reaches a certain age, there should be a point at which people with a fervent interest in it, who have studied it so intensively, should be able to view it and offer their opinions,” Barth said.

Vaughn and her crew filmed much of the episode on Bundy with the help of Barth, who took them to locations in Ocean City and Somers Point during the production.

With “Violent Minds: Killers On Tape,” Vaughan hopes that the stories told honor the people killed in these gruesome crimes.

“They’re still important to people. That really means a lot to us, and I think it would mean a lot to Dr. Carlisle,” Vaughan said. “It’s hard to think that 50 years later, you could say, with 1,000% certainty and the definitiveness of DNA, ‘This case is closed and Ted Bundy did it.’ That’s hard to imagine, but it doesn’t mean you can’t get more answers than you’ve ever gotten and feel like there is some sort of closure and justice.”

“Violent Minds: Killers On Tape” airs Sundays on Oxygen. Those with cable, digital or satellite TV subscriptions, can be stream episodes via the Oxygen app. The second hour of the premiere, Episode 2, features Bundy and the Garden State Parkway murders. Most Oxygen shows also are available on Apple TV+, Amazon Fire TV, Roku and through Chromecast. Individual episodes can be purchased on iTunes, Amazon, Vudu and Google Play, as well. Oxygen has uploaded the first two episodes of the series on its YouTube page. Those episodes can be viewed below.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by PostX News and is published from a syndicated feed.)